Indigenous democracy (Story of Tlaxcala 1500CE)

About organized decentralized cities in Meso America, without kings, queens and “supreme leaders”.

“The 250,000 people of Tlaxcala live without a king or supreme leader…no sign of a palace or ritual court…” wrote Fransisco Cervantes de Salazar in 1556 CE (Crónica de la Nueva España). The book remained unpublished until 1914. In the above observation, Fransisco Salazar was expressing awe at a form of indigenous democracy, within urban spaces dotted allover central Mexico. As a first time for European eyes, the complex but non-hierarchical society of Tlaxcala was a sort of paradigm shift that European historians such as Bartolome de Casas, Antonio Carlos Hererra and Amerigo Vespucci had completely missed. A Spanish humanist, religious scholar and historian, Salazar born in Toledo, educated in Salamanca, was the first to record the centuries long resistance by the people of Teotihuacán and later by Tlaxcala against the Aztec empire.

Early accounts of highland Mexico, before and after the Conquistadors had destroyed the mighty Aztec Triple Alliance reveals the existence of many autonomous societies spread around the empire. Organized yet decentralized cities without kings, queens and “supreme leaders”. Yes wars were waged, slaves exchanged, ritual human sacrifices made, apartments constructed, temples and water ways commissioned, backed by trade, commerce and agriculture (without cattle and metal tools). We find remains of organized life which thrived for hundreds of years, before the arrival of the Spanish. What is known today as a “detonator event” was blessed back then as “manifest destiny” - of the colonizers, who carried with them the seeds (of deadly change) summed up as “Guns, Germs and Steel” (Jared Diamond). But lets go back to Tlaxcala, an “indigenous republic” with democratic credentials and “well appointed citizens”. How did they as a society face not one but two “predatory empires” (the Aztecs and the Spanish)?

We often ‘imagine’ Meso-American or indigenous societies of South America to be top-down, pyramid like societies, crowned by an emperor, warlord, head priest, chieftain etc. Mainstream history frames the Spanish discovery of the “New World” as a “clash of civilizations” or “manifest destiny” extending into centuries of conquest, genocide, slavery, extraction and conversion. That is surely shocking but incomplete and misleading. The empires of the Aztecs, Mayas and Incas were surrounded by many equally advanced societies, smaller in size and many times without standing military power. That aspect of organized life, impressed and influenced not only Fransisco Salazar but almost every Spanish and European colonizer, priest and historian who visited “Nueva España” after the fall of the Aztec empire, almost 65 years after Christopher Columbus had discovered The Bahamas and West Indies, which to his dying day he believed was India! Salazar, who came to be the first rector of the newly established university of Mexico City (then known as Tenochtitlan Mexicana) dedicated a significant part of his career to document the rise and fall of Teotihuacán and the surviving state of Tlaxcala. 500 years on, that record of antiquity is being enriched by new archeology, anthropology and revival of Meso-American culture and history.

Tlaxcala came about from the legacy of Teotihuacán, concluded Salazar back then as do many archeologists and historians of today. Teotihuacán, was one of the largest cities of Meso-America. Its foundation dates back to the time when the Roman empire was at its zenith (200 CE). The enormous city at it’s prime was spread across 3600 hectares, converging at the site of three pyramids, the temples of the Sun, the Moon and the Feathered Serpent. Built between 350-450 CE, the three pyramids were the central landmarks, nested within open air public spaces, hosting ceremonies including the annual spectacle of “ritual killing”. Bodies and heads of the sacrificed were placed at the corner of the the three pyramids. Teotihuacán ruins show single-story apartment buildings with drainage and central courtyards. Unearthed murals in Teotihuacán reveal a “wide range of social activities, customs and rituals… a quasi-state that appears way more egalitarian and progressive than the dominant European models of the time.“ (Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow).

Much like Athens, Rome, Constantinople and Jerusalem, Teotihuacán was eventually invaded, sacked and raised to the ground, and the three temples were burned by the Aztecs (560 CE). Historian Thelma Sullivan interprets the name Teotihuacán as "the road to where live the gods”. Aztecs believed that the gods created the universe at the site of Teotihuacán. Those who could evade Aztec slavery, domination or outright slaughter fled into the hinterland, heading into regions now known as Puebla, Xalapa and Potosi. Somewhere around mid-9th century Tlaxcala came to prosper as a site, where various indigenous outliers of the Aztec empire managed to form alliances and set new egalitarian rules, to settle their growing numbers. More than 1000 different sites have been unearthed which mark the extent of this alliance. The Spiral Pyramid reminiscent of the mythical Teotihuacán, but way more spacious and advanced in terms of construction.

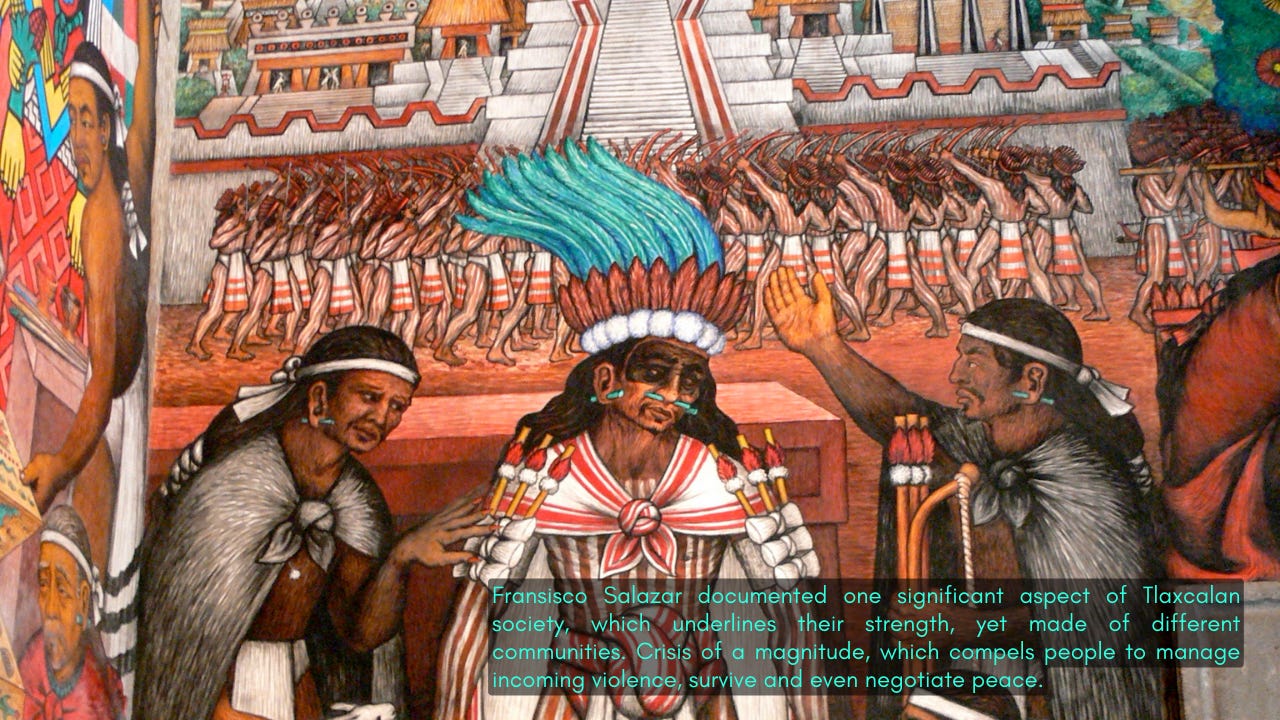

Fransisco Salazar documented one significant aspect of Tlaxcalan society, which underlines their strength, yet distributed within different communities. Crisis of a magnitude, which compels people to manage incoming violence, survive and even negotiate peace. The Aztec empire which surrounded Tlaxcala from all sides, repeatedly attacked but never managed to conquer the region. All that went relatively well, until the Spanish arrived. Lead by Hernán Cortez and roughly 900 soldiers, it makes for a crucial moment in history and exhibits the resilience of Tlaxcalans.

This happened somewhere between 1517 and 1518. Cortez backed by a budget of ‘Guns, Germs and Steel’ had managed to invade highland Mexico, killing thousands of indigenous people, still hovering around the outer limits of the Aztec empire, laying siege on the city of Tlaxcala. The people of Tlaxcala had never ever seen Europeans, worse unaware of the deadly threats that the Spanish yielded upon their arrival. The centuries long threat of Aztec domination, was abruptly replaced by a new possibility of near term extinction! Even as the conquistadors blessed by the holy cross and “manifest destiny” had suffered big losses, the Tlaxcalans knew that their end was near, if peace was not negotiated immediately.

We cannot be sure if it was the people or their chosen leaders, within each community which marked the alliance of Tlaxcala, that came up with a ‘win win proposition’ for themselves and the invaders. ‘Win win’ with a fair amount of violence to be precise. According to Spanish historian Diego Muñoz Camárgo, Xicotencatl the Younger offered a settlement to the Spanish, not as an enemy but as a friend. Xicotencatl pledged to help the Spanish defeat the Aztecs, in return for peace and autonomy for the people of Tlaxcala and their land. Internally the Tlaxcalans had decided “that it would be better to ally with the Spanish than try to kill them and also be destroyed in the act...” (Crónica de la Nueva España). Hernán Cortez could not have expected a better “manifest destiny” and no thanks to him nor Jesus, but the terror struck natives.

The outcome of many succeeding events would be vastly different, if this crucial deal between two races had not been struck. Fransisco Salazar’s ‘Crónica de la Nueva España’ managed to record this “unique point in history, where the council of Tlaxcala and the Spanish negotiated, while exchanging of gifts and weapons before arriving at the final deal..” (Gun, Germs and Steel - Jared Diamond). Either way, this 'model of colonization’ set the wheels rolling for not just the Spanish, but also for the Portuguese, French, Dutch and British for the next 300 years in many parts of the world. Cortez and the remaining famished Spanish soldiers with their remaining ‘Guns, Horses and Steel’ would have never managed to topple the Aztec empire (about 4 million citizens and a sizeable army) without the outstanding military support of the Tlaxcalans, who also rallied other outlying indigenous groups in the north and south of Mexico to join forces and overthrow the Aztecs, leading up to the sacking and fall of Tenochtitlan (Mexico City) in July 1521. Across the Atlantic, in Spain as news came through, the Grand Inquisitor clasped his hands together, rapt in visions of ‘El Dorado’ (land of gold) and eternal fountains of life bearing elixirs, all be it in the name of almighty God (and the ravenous empire).

Where the Meso-American timeline starts to fade and Spanish colonization begins to surge out is a blurry space. The next 150 years would mark the wildest ‘free run’ in terms of European colonization. Spanish discovery, conquest, extraction, slavery and loot, all feeding an unstable greedy empire which would eventually disintegrate into thousands of mutinies across South, Central and North America during the succeeding 150 years. During that epoch, the world would also drastically transform. Replete with pioneering voyages, leading to conquest, devastation and loss. That continuum of world making and world destruction, would mark the fate of Tlaxcala as well. The people of Tlaxcala would eventually fade into the emerging Mexican state. And so would their autonomy and social structures which had thrived for hundreds of years. Even as the Tlaxcalans evaded slavery, disease and conversion to an extent, they would simply perish in numbers including their dialect itself.

Today, Tlaxcala and Teotihuacán are not only hotspots for anthropologists and historians, but also loads of foreign tourists, fortune hunters as well as indigenous peoples of Nahuatl, Maya, Mixtec, Zapotec, Otomi origin who believe that their ancestors were from Tlaxcala or Teotihuacán. The sites attract many visitors, as a Machu Picchu (Peru) or Cholula (Mexico) does, which are the preferred sites of Meso-American empires. Less we forget, Tlaxcala was never an empire nor a kingdom. The history of Teotihuacán shows no clear lineage of kings. Both societies were quasi democratic, a cluster of societies held together by people, operating within a wise set of conventions.

The takeaway?

Speaking of decentralized and sustainable societies, the above history provides us with one useful convention, that we may have forgotten today. That top-down authoritarian rule is not a natural outcome, nor does it lead to better organization and control. Self conscious egalitarian systems work, even when thousands of people are involved. Entire cities containing multiple societies serving multiple interests appeared many times during our history, across the world. Some of them were indeed democratic and egalitarian, without the need to define a nation or state. Yet those systems and institutions of organization did not look nor function like the type of democracy we have come to believe in (and accept) today.

I love your writing style, Counter. "‘Win win’ with a fair amount of violence to be precise." I love the idea that there's no evidence of a lineage of rulers in this area. Perhaps the "pillars of the community" would arise as conditions required to accomplish all the defense and public (presumably) building of infrastructure.

I had the pleasure of spending part of the day in Teotihuacán many years ago. Later in a small museum in Vera Cruz they had a display that suggested it was the much earlier Olmecs that build the pyramid complex. Is that what your reading suggested or is it more complex?

Many thanks for sharing!